iPartners inFocus - Australia In 2023: Risks & Issues

Michael Blythe's latest iPartners inFocus examines the Australian and worldwide economies that failed to meet expectations in 2022 (again). (By Michael Blythe, 9th December 2022)

- The Australian and global economies failed to live up to expectations in 2022 (again).

- Uncertainty prevails at the start of 2023 (again).

- The global economy may skate past the recession – but it will feel like it in some countries.

- The Australian economy will slow in an absolute sense but outperform in a relative sense.

- A cash rate peak above 3½% would significantly increase the risk of recession in 2023.

- The labour market will provide the best read on how the opposing forces are playing out.

Economists are prone to observe that the future is “uncertain”. At times of great stress, economists will often offer up a warning that “the future is more than usually uncertain”. Sage advice. And an accurate description of the evolution of economic prospects during 2022.

It’s also advice that policy makers, economic commentators, and politicians should keep in mind during 2023. Economic outcomes disappointed in 2022. And the risks of a repeat performance in 2023 are elevated.

The global economy is set to grow by around 60% of its “normal” (or pre-Covid) growth rate in 2023. Disappointing. But not a recession.

The Australian economy is set to grow at about 75% of normal. So slower than in 2022. But better than many economies will experience in the year ahead.

Rear view

The conditions for a sustained recovery – both in Australia and the rest of the world – were falling into place at the start of 2022:

•Economies were bouncing back as Covid-related restrictions were eased.

•Monetary and fiscal policies were at the stimulatory end of the range.

•Geopolitical concerns were generally muted.

•There were some indications that inflation pressures were stirring. But the consensus view was that these pressures were transitory and would soon subside.

•Some central banks were lifting interest rates. These increases were about moving away from “emergency” levels rather that shifting to inflation-fighting mode. RBA Governor Lowe, for example, was telling anyone who would listen that any lift in Australian interest rates was unlikely before 2024.

From an Australian perspective, this mix was expected to deliver GDP growth of better than 5% in 2022. And growth in Australia’s major trading partners was put at a trend-like 4%pa or better (Chart 1).

But then a series of “shocks” changed the trajectory for Australia and the rest of the world.

The Russian invasion of the Ukraine generated a geopolitical shock that quickly morphed into an energy price shock.

And a food price shock. Higher energy and food prices contributed to an inflation shock more broadly. Households are dealing with a cost-of-living shock. And central banks created their own shock by lifting interest rates aggressively. Higher policy rates bring up the possibility of debt repayment and economic growth shocks as well.

Forecasters responded by slashing growth expectations for the Australian economy and the rest of the world.

Australian growth estimates for 2022, for example, now stand at only 2.9% (Chart 1 again). Unsurprisingly, inflation forecasts moved higher. Surprisingly, the labour market remained a bright spot and the expected unemployment rate moved lower (Chart 2).

These shocks remain in play at the end of 2022. How they get resolved will determine the economic path in 2023.

So the starting point for the year ahead is one of downside risks and elevated uncertainty.

For an economist with too much time on his hands what stands out is the number of mentions of “risk” in recent outlook

publications (Chart 3).

The global backdrop

Inflation rates lifted everywhere in 2022 (Chart 4).

The direction of inflation is the key uncertainty in the outlook for the global economy. The inflation high point will determine how far central banks go. How quickly inflation rates turn down will determine the duration of peak policy rates. The policy rate peak and duration will determine the extent of downside risks to global economic activity.

The risk lies with a global recession in 2023:

• The share of OECD GDP spent on energy use is above the levels recorded in the oil shocks of the mid 1970s and early 1980s. Those earlier shocks were associated with global recessions (Chart 5).

• Central banks have pushed through an aggressive series of interest rate rises. And there is more to come. The number of central banks delivering unusually large interest rate rises (that is, more than 25bpts per decision) is at a record high (Chart 6). The risks of a policy “mistake”, and an ensuing recession, are rising.

• History shows it typically takes a recession to deal with entrenched inflation pressures (Chart 7).

Inflation pessimism reigned for much of 2022. And there was a continuous process of upward revision to estimates of policy rate peaks. But, late in 2022, there were some tentative signs that this pessimism was overdone. And expected interest rate peaks were too high.

The US remains central to the global economy and financial markets. Watching US inflation trends is the key to assessing inflation and interest rate risks.

The lift in US inflation rates is quite broadly based. Around 55% of CPI components are running above 6%pa. But it is a much “narrower” picture in terms of contributions to the acceleration in the inflation rate.

The major CPI expenditure categories of Housing, Transport, Food & Beverages, and Medical Care account for 93% of CPI growth over the past year.

The good news is that leading indicators of these US CPI components are pointing lower. The better news is that these indicators suggest a rapid deceleration is possible.

The momentum behind the Zillow Observed Rent Index, for example, has swung into reverse. Growth in rents should follow suit (Chart 8).

Growth in global food price indicators has slowed sharply. This slowing will flow through to the relevant CPI components (Chart 9). Lower oil prices will help reduce household energy and fuel costs. An easing in supply chain constraints will increase supply and reduce motor vehicle price pressures.

Beyond the specific inflation drivers, the macro environment is evolving in a way that favours lower inflation rates as well:

•Global shipping costs have retraced back to pre-COVID levels (Chart 10). This reduction is another sign of easing supply-side constraints that were an important driver of the inflation uplift.

•Growth in Chinese wholesale prices is slowing. The inflation impetus from rising import prices in the advanced economies should keep receding as a result (Chart 11).

The potential for a speedy deceleration in inflation as these forces work through is helped by the simple mathematics.

For the mathematicians, the annual inflation rate is roughly equal to the sum of the twelve individual monthly CPI outcomes.

So, the inflation rate will slow if the new monthly CPI outcome being added is lower than the one “dropping out” from a year earlier. This influence will increasingly come into play as the large monthly rises of late 2021 to mid 2022 fall out of the annual growth calculations.

A quick back-of-the-envelope calculation highlights the point. Assume that the average CPI increase of 0.8% per month from October 2021 to June 2022 is replaced with the 0.2% per month average evident since July. This mix would mean that US CPI inflation would slow from a peak rate of 9.1%pa in mid 2022 to only 2.5% by mid 2023.

Central bankers are aware of all these influences and how they may play out. They remain cautious and clearly expect to lift policy rates further. But the “guidance” now coming through is that prospective rate rises will be smaller than those seen earlier in the cycle. They note that the impact of earlier rate rises is still working through.

Financial markets are responding. Estimates of peak interest rates have been scaled back a little. Near the end of 2022:

•The CBOT futures market, which provides an indication of where markets expect the US Fed funds rate to go, is pricing a peak of 4.9% by mid 2023 (Chart 12).

• US bond yields and estimates of term premiums put the terminal Fed funds rate (10yr bond less term premium) at 4.4%.

The Fed funds rate currently stands at 3.75-4%. If the market is right, then the peak is not far off. And the global economy may be able to skate past a full-on recession.

But financial market players also remain cautious.

The yield curve reflects views on where the economy is going and how monetary policy settings may change. The practical upshot is that the slope of the yield curve provides a measure of what markets are pricing in for the risk of recession. The Fed Reserve of New York has constructed a recession probability indicator based on the US curve (Chart 13). Current readings place the probability of a US recession over the next year at a relatively high 23%.

Slowing inflation and elevated recession risks are reasons why financial markets expect interest rate cuts in the second half of 2023 (Chart 12 again).

Policy makers also have fiscal levers they can pull. But the contribution that fiscal policy can make is limited by the massive increase in public debt as governments combatted the pandemic. OECD general government gross financial liabilities increased by more than 20% of GDP in 2020. The policy focus has inevitably turned to fiscal consolidation. Too fast a consolidation would be a threat to economic activity.

Fiscal consolidation was particularly large in 2022, reinforcing the drag from tighter monetary policy (Chart 14). But current policy settings suggest only a modest fiscal drag in 2023 and 2024.

The global economy may skate past a recession in a statistical sense. But the experience will vary between countries. And certainly, in some economies, it will feel like the real thing.

The global economy is set to grow by around 60% of its “normal” (or pre-Covid) growth rate in 2023 (Chart 15). Disappointing. But not a recession.

The major economies fare worse. Forecasts have that group growing at only 29% of normal. It will feel like a recession. And in some countries, it will be the real deal (Germany and the UK, for example). Australia stands out against the major economies – forecasts put growth in 2023 at 75% of normal.

Emerging economies fare better (or at least less worse). China, at 60% of normal, lies towards the lower end of the range.

The strong USD is a particular risk to emerging economies. The US currency strengthened during 2022 on a combination of interest rate rises, safe-haven flows and economic outperformance. The average USD Index in 2022 was more than 8% above the level in 2021.

A rising USD makes it more difficult for EM economies to service their USD-denominated debt. EM bond spreads tend to widen as EM currencies weaken. EM commodity exporters are hurt as a stronger USD tends to depress USD-denominated commodity prices.

In the advanced economies, households are facing a perfect storm. High inflation rates are pushing up living costs and pulling down real wages. Higher interest rates designed to fix the inflation problem are hurting borrowers. And the limited fiscal space means limited government ability to help.

To end on a slightly more positive note, there are some upside risks for the global economy.

Potential upside risks include a reduction in uncertainty, perhaps reflecting a resolution of the Russia-Ukraine conflict. Risk premia would fall and consumer confidence may improve. Key commodity prices like oil and wheat would weaken if supply improved.

The OECD has simulated a scenario where risk premia drop by 100bpts, oil prices fall by 10% and food prices ease by 5%. The outcome would be global growth 0.4-0.5bpts above the current baseline. And global inflation rates would be lower (Chart 16).

The Australian Economy

The global shocks were fully transmitted through to the Australian economy.

Australian inflation rates also accelerated in 2022. The latest readings are running around 7%pa in headline terms. And more than 5%pa on an underlying or core basis. Inflation outcomes are around the highest since the early 1990s.

The RBA may have been a little late in joining the rate-rise party. But a series of larger-than-usual rate rises makes this cycle one of the largest and most aggressive of the past three decades (Chart 17).

As elsewhere, households are the epicentre of the various shocks hitting the Australian economy. The cost of living regularly tops polls of what concerns Australians.

The additional global transmission channel that will influence Australian growth prospects is commodity prices.

As already noted, a strong USD is a negative in the commodity price story. Weak global growth (Chart 18) and the unwinding of the quantitative easing measures pursued by the major central banks are also downside price risks. The net impact of these influences is a commodity price profile that should be flat-to-down over the next year.

A lower AUD is the typical shock absorber when the commodity story turns against Australia. Nevertheless, lower commodity prices will mean a weaker terms-of-trade and slower no\5`1minal GDP growth.

Nominal GDP represents total Australian income. And weaker income would be a negative for government revenues and business profits in particular.

Australia is subject to the same forces as the rest of the world. But as things stand at the end of 2022, the Australian economy is exhibiting a greater degree of resilience.

Our online activity, for example, is close to a real-time indicator of economic activity. The OECD have taken this idea and used information from Google to develop a weekly GDP “Tracker”. The Tracker applies a machine-learning model to Google Trends search behaviour related to consumption, labour markets, housing, trade, industrial activity and economic uncertainty. Latest readings show the Australian economy outperforming the major economies (Chart 19).

This outperformance is set to continue into 2023. GDP growth is projected to slow. But the deviation from normal is less than expected in the major economies. And there are some hot spots like the rural sector. Unemployment is expected to rise. But the rise would leave the unemployment rate not far from fifty-year lows.

RBA projections often form the baseline for the private sector

consensus (Table 1 & Chart 20). These projections have the Australian economy running at a sub-trend 1.4%

through 2023. In detail:

• Slower GDP growth reflects households cutting their spending on consumer items and residential construction.

• The public sector is also a drag as the extraordinary fiscal support of recent years unwinds.

• Business capex is one of the few bright spots in the overall growth trajectory.

• Import growth slows more than exports so net external trade actually makes a positive contribution to growth.

• While GDP growth is slowing, it remains sufficient to limit any real damage to the labour market.

• Inflation rates are set to peak at the end of 2022 and slow through 2023.

The key to turning these projections into reality is success in the fight against inflation.

The idea that inflation rates are at or near a peak has already allowed the RBA to move from larger-than-usual rate rises to the more “normal” 25bpts. They are one of the first global central banks to make that downshift.

Financial market pricing gives some insight at to where official interest rates may peak:

•The Overnight Index Swap market (OIS), which provides an indication of where markets expect the RBA’s cash rate to go, is pricing a plateau of 3.2-3.4% by mid 2023.

•Australian bond yields and estimates of term premiums put the terminal RBA cash rate (10yr bond less term premium) at 3.3%.

The cash rate currently stands at 3.1%. If the market is right, then the peak is very close. The RBA next meets in February 2023. No doubt borrowers will sigh with relief, for now.

As with the earlier analysis of US CPI inflation prospects, the good news is that a variety of leading price indicators pointing lower. Australian financial markets have been able to price in some chance of rate cuts late in 2023 / early 2024 as a result.

The favourable inflation indicators are coming through a variety of fundamental and item-specific channels.

On the fundamentals, the OECD has constructed estimates of the demand and supply influences on the consumption price deflator. The analysis shows that the acceleration in inflation over the past year reflected in equal measure demand and supply influences.

Looking ahead, demand-pull inflation should ease as the economy slows. And cost-push inflation should slow as supply chain constraints (including the recent floods) dissipate.

On the specifics, the acceleration in inflation over the past year was broadly based. But, as with the US, it is a much “narrower” picture in terms of contributions to the acceleration in the inflation rate. The major CPI expenditure categories of Food, Housing and Transport account for nearly 70% of CPI growth over the past year.

Looking ahead, the downturn in the housing market and reduced residential construction should see growth in housing-related inflation slow sharply (Chart 22).

Lower oil prices will help reduce household transport costs (Chart 23). The main flies in the inflation ointment are the recent floods – which will delay the flow through of lower global food prices. And gas & electricity costs – which are yet to fully reflect the lift in global energy prices.

Nevertheless, expected inflation trends support the idea that the cash rate is near the peak and that rate cuts are possible late in 2023. On that point, history shows that the time spent at the interest-rate peak is relatively short. The average time at peak rates over the last 4 policy cycles is 11 months (Chart 24).

These considerations are important because, in the end, it is the level of interest rates that does the work on the economy.

So one of the key questions for 2023 is what is the critical level of rates that would produce a significant impact on the economy.

At one level we already know the answer. The RBA has moved rates far enough to produce a “housing recession”. Dwelling prices began falling in May 2022. Residential construction indicators had rolled over late in 2021, well before the RBA stepped up to the plate.

The “typical” house price downturn involves falls of 4½-8½% (2008, 2010, 2017 in Chart 25). And the typical downturn runs for 4-6 quarters.

Dwelling prices close to the end of 2022 were about 7½% below the peak. The consensus among the major banks is that dwelling prices will fall a further 8% in 2023 (Table 2). The peak-to-trough decline would be of the order of 15%.

A 15% decline would be exceptional given the experience of the past couple of decades (Chart 25 again). The downturn to date is faster than previous cycles. But some balancing forces are coming into play. These include:

• The return of migrants and foreign students will boost demand. Overseas migration looks set to return to the pre-pandemic norm of 200-250,000 (Chart 26).

• The downturn in housing construction is reducing new supply.

• The increase in the RBA cash rate is not being fully passed-on to new borrowers. The housing loan indicator rate lifted by 225bpts from April to September, fully matching the RBA. But the rate for new borrowers is up by a lesser 188bpts.

• Sentiment towards housing is in negative territory. But the decline has ended.

• The auction clearance rate has stabilised/increased over the past couple of months.

The consensus on a 15% peak-to-trough price fall is starting to look a little pessimistic.

The other component of the housing recession is falling residential construction. Housing construction cycles tend to be large. So residential construction can have an outsize impact on GDP growth (Chart 27). Construction downturns over the past 15 years have knocked ½-1%ppts off GDP growth. The current downturn is set to fall somewhere in that range. The return of migrants and foreign students should limit the downside.

A housing recession is one element that lifts the risk of a “consumer recession”. Falling dwelling prices cut household wealth. Falling wealth can mean less spending and weaker consumer confidence. Falling residential construction directly impacts on consumer spending. Fewer new houses mean less demand for furniture, carpets, and other household durables.

The bigger risk leading to a consumer recession relates to a household's ability to spend. The drag from falling real wages should ease as wage growth lifts a little and inflation rates slow a lot (Table 1). The saving ratio is still above pre-pandemic norms – so saving less remains an option to fund spending. But the reduction in household spending power as debt servicing costs rise could be large.

A rising debt service ratio (DSR) reflects the lift in the RBA cash rate. And the refinancing hit coming as the very low fixed rates of the past few years roll off. New rates on three-year fixed-rate loans are about 3% higher than the rates available three years earlier (Chart 28). That will be a significant repayment “shock”.

Consumer recessions are rare. The last was in 2008 when consumer spending actually declined (shaded area on Chart 29). That consumer recession was associated with a lift in the DSR to 10% of disposable income. And that lift also contributed to a sharp increase in the home loan impairment rate (Chart 29).

The question for analysts is what interest rate settings will get the DSR up to that critical level and precipitate a consumer recession?

The main inputs into the equation are:

•Modelling work by PinPoint Macro that indicates each 1% rise in the RBA cash rate boosts the DSR by 0.8%. So the 300bpts worth of rate rises to date will lift the ratio to 6.8%.

•Market pricing has one-two more 25bpt rate rises pencilled in before the peak rate is reached. That final rate step will lift the DSR to 7.2%.

•The extra wrinkle this time is the unusually large share of fixed rate home loans. RBA analysis put the share of housing debt on fixed rates at 40% early in 2022 (vs more normal levels of 20%). The fixed loans are rolling off with the biggest impact likely in the second half of 2023. If the fixed rate lending share drops back to 20%, then the interest rate impact would be equivalent to an 0.6% rise in the RBA cash rate (20% x 3%). That extra rise would lift the DSR to 7.7%.

The calculations suggest that the RBA will stop short of the rates that would push households over the edge (Chart 30).

This cautious stopping point makes sense. The monetary authorities are not aiming to push households into extreme stress and generate a consumer recession. Nor are they aiming to generate risks to financial stability by collapsing the housing market.

But the margin for error is small (Chart 30 again). It wouldn’t take too many rate rises beyond the 3½% cash rate peak currently envisaged to provoke a consumer recession.

Consumer activity reflects more than just the trends in debt servicing. The labour market is also important.

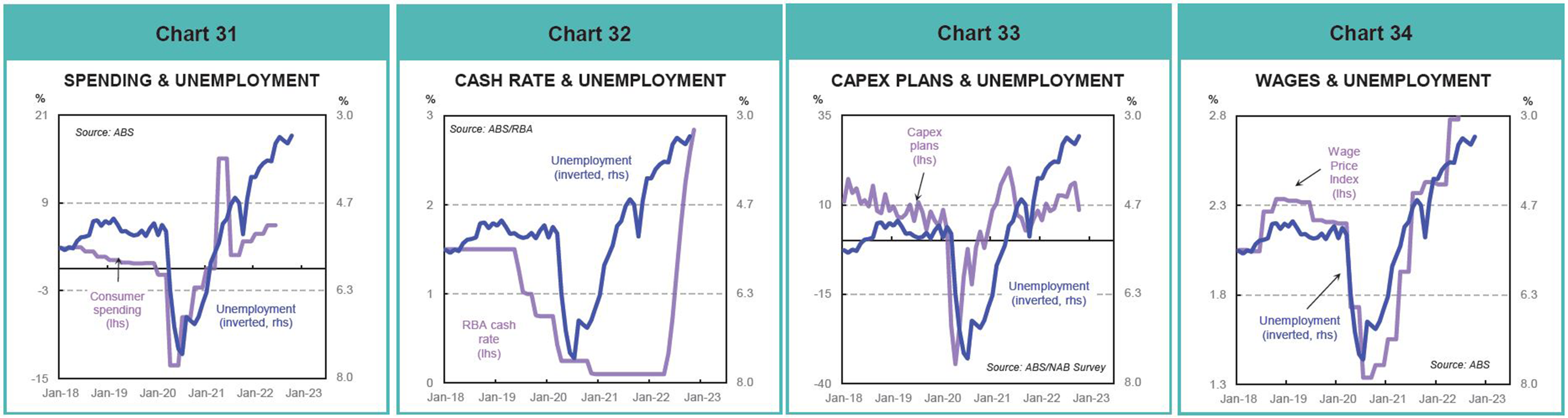

Having a job generates income. Having a job is important for calming job security fears and boosting confidence. The unemployment rate balances out demand and supply in the labour market and feeds back into wages growth. In fact, the labour market provides a series of all-purpose indicators that show the economic pulse and how the balance of risks is evolving (Charts 31-34). So, watch the labour market closely in 2023.

Some thoughts on financial markets

The iPartners inFocus piece looking at the “Secrets of a bond market strategist” is helpful in translating the expected economic fundamentals into a financial market roadmap. Some illustrative results are shown in Table 3. Shorter-term interest rates should closely follow the RBA trajectory. So the risk is higher rates in the first half of 2023 before some retracement in the second half.

Longer-term rates typically reflect US trends and policy rate differentials. This mix of drivers should see longer-term rates declining in the second half of 2023.

The key fundamentals that drive the AUD are the terms-of-trade (or commodity prices), interest rate differentials, and the current account balance. The net impact is likely to be negative for the Aussie in the first half of the year. And more neutral in the second half.

Lower commodity prices and a profit squeeze as GDP growth slows and costs rise provide a negative lead for Australian equity markets in 2023.

Meanwhile I’m off to buy a crystal ball and have a look at 2024!